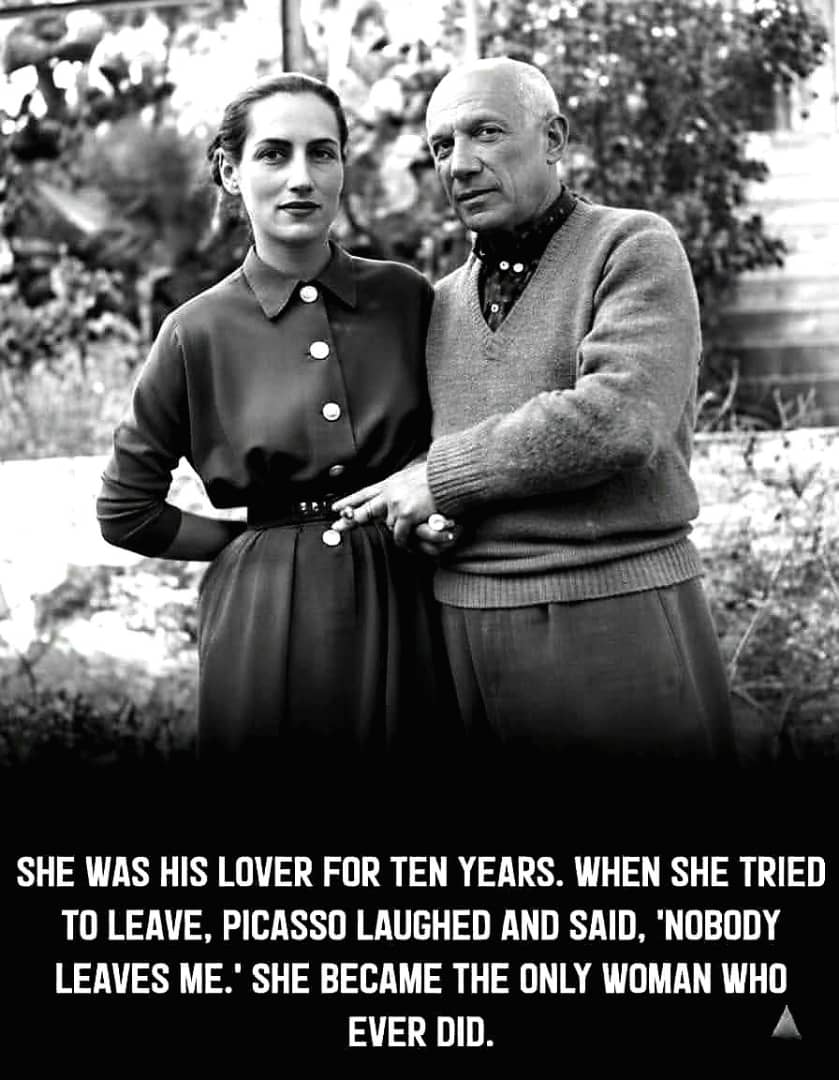

She was 21. He was 61. And when she tried to leave him, Pablo Picasso looked at her and laughed: “Nobody leaves Picasso.” She left anyway—and became the only woman who ever did.

Pablo Picasso didn’t just love women. He consumed them. He destroyed them. Literally.

Marie-Thérèse Walter, his lover, ended her life four years after his death—unable to exist without him even in memory. Dora Maar, the brilliant photographer immortalized as “The Weeping Woman,” spent years in psychiatric care after he discarded her. Jacqueline Roque, his second wife, shot herself thirteen years after he died.

The pattern was always the same: Picasso found a young, talented woman, devoured her youth, her art, her identity, and painted her obsessively. Then, when he was finished, he moved on.

He called women “goddesses or doormats.” He also called them “machines for suffering.” For decades, no woman escaped him. They either stayed until he left, or they broke trying.

Until Françoise Gilot.

Paris, 1943. The city dark, occupied by Nazis, cafés half-empty, tense. In one smoke-filled room, 21-year-old Françoise—a painting student with fierce intelligence and fiercer eyes—met the 61-year-old Picasso.

He looked at her and said, “You’re so young. I could be your father.”

She met his gaze without flinching. “You’re not my father.”

That was Françoise—steel wrapped in grace.

For ten years, she lived in his orbit. She painted. She loved him. She bore him two children—Claude and Paloma. He painted her hundreds of times, called her his muse, his “woman who saw too much.”

But Françoise saw the trap.

“I loved him,” she later said, “but I also saw how he needed to destroy the thing he loved most.”

By the early 1950s, the mask had slipped. Picasso—once charming, once brilliant—had become cruel. He demanded worship, not partnership. Every conversation a struggle, every silence psychological warfare. He pitted her against his other women. Belittled her art. Raged at her independence.

Other women had crumbled under this. Dora Maar had tried to resist and ended up institutionalized. Marie-Thérèse had accepted the role of perpetual mistress, waiting for scraps of attention.

Françoise was different.

One morning in 1953, after another night of shouting and manipulation, she stood in their Vallauris villa and faced herself in the mirror. She was 32, but felt ancient. Behind her, Picasso’s paintings covered every wall like watchful eyes.

She turned to him and said quietly, “I’m leaving.”

Picasso laughed. Cold, disbelieving—the laugh of a man who had never been refused.

“You can’t leave me. Nobody leaves Picasso.”

She left anyway. Quietly. Packed her things, took her children, and walked out of the villa, out of his shadow, out of his control. No drama. No breakdown. Just the quiet power of a woman reclaiming her soul.

“I wasn’t a prisoner,” she said later. “I came when I wanted to—and I left when I wanted to.”

Picasso was stunned. Furious. He tried to destroy her. Told gallery owners across Europe and America never to show her work. Spread rumors she was unstable, ungrateful, nothing without him. “People will never care about you,” he sneered.

But Françoise refused to vanish. She painted. Raised her children alone. Rebuilt her career, gallery by gallery, painting by painting.

In 1964, she published Life with Picasso—an unflinching memoir exposing his cruelty. Critics called it vengeful; Picasso’s friends called it betrayal; Picasso himself tried to ban it. Françoise called it freedom.

“I owed the truth to other women,” she said. “So they would know they could survive him too.”

The book became an international bestseller. The world finally saw behind the genius—the manipulation, the destruction, the power wielded over the women who loved him.

Years later, she found love again—with Dr. Jonas Salk, the virologist who developed the polio vaccine. “Picasso wanted to possess the world,” she said. “Jonas wanted to heal it.” She married Salk in 1970; they remained partners until his death in 1995. With him, she experienced respect, partnership, and love—not domination.

Meanwhile, her art flourished. Vibrant, strong, unapologetically hers, her work appeared in the Met, MoMA, Centre Pompidou. Her paintings spoke of survival, resilience, and rebirth.

She became exactly what Picasso feared: remembered for her own brilliance, not his.

Picasso died in 1973 at 91, wealthy and surrounded by art, but alone. Françoise lived until 2023—dying peacefully at 101, outliving him by fifty years. In those years, she painted, taught, inspired, watched her children and grandchildren thrive. She proved that a woman could survive Picasso and emerge not as a footnote, but as a force.

Asked late in life how she found the courage to leave, she said simply:

“Because freedom is the only love worth keeping.”

Picasso painted her face hundreds of times, trying to capture, control, and own her.

Françoise painted her own destiny.

She was 21 when she met the most powerful man in the art world. 32 when she walked away. 101 when she died—having spent seventy years proving she was never his muse.

She was always the artist.

Pablo Picasso destroyed every woman he touched. Except one.

Françoise Gilot didn’t just survive Picasso. She walked out of his shadow and into her own brilliant light—and stayed there for the rest of her extraordinary life.

Sometimes, the greatest act of creation is refusing to be destroyed.”

© Ancient History